here’s something quietly enchanting about Immanuel Kant. Picture a slight, unassuming man in the Prussian town of Königsberg, taking his daily walk at precisely the same hour each afternoon—so punctual that the locals supposedly set their clocks by him. He never traveled more than a few miles from home, never married, and lived a life of almost monastic routine. Yet from this small corner of 18th-century Europe, he sent ripples that reshaped how we understand knowledge, morality, and even beauty itself.

Kant was born in 1724 into a modest, deeply pious family. His early years were steeped in Pietism, a Lutheran movement that emphasized personal devotion and moral rigor. Though he later drifted from organized religion, that early grounding in duty and inner conviction never left him. He studied at the local university, tutored to support himself, and eventually became a professor—beloved for his lectures, which drew crowds long before his books made him famous.

Image credit: https://www.trinitymethodist.org.nz/post/immanuel-kant-1724-1804

Kant’s great awakening came, by his own admission, from reading David Hume, who “roused me from my dogmatic slumber.” Until then, philosophy had been split between rationalists (who believed pure reason could unlock the universe) and empiricists (who insisted all knowledge comes from experience). Kant saw the strengths and blind spots in both. His response? A quiet revolution, often called his “Copernican turn”: instead of asking how our minds conform to the world, he asked how the world (as we know it) conforms to the structures of our minds.

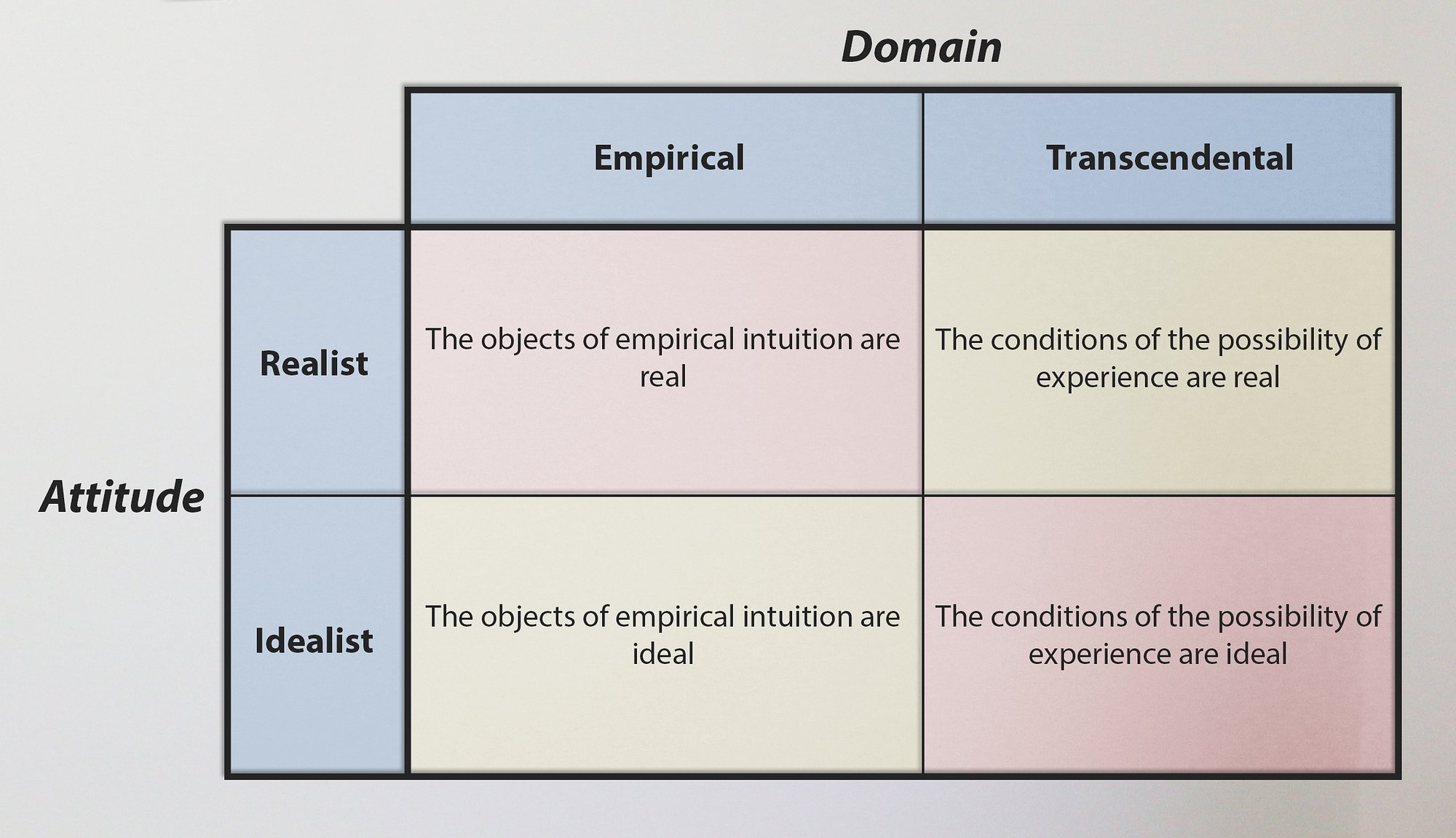

This idea lies at the heart of his masterpiece, the Critique of Pure Reason (1781). We don’t passively receive reality, Kant argued; our minds actively shape it. Space and time aren’t “out there” waiting to be discovered—they’re the built-in lenses through which we experience everything. We can know the world of appearances (phenomena) with certainty—think mathematics, physics, the reliable laws of nature—but the ultimate reality behind those appearances (the “things-in-themselves,” or noumena) remains forever beyond our grasp.

Image credit: medium.com

t’s a humbling thought: we’re both masters and prisoners of our own perception.

But Kant didn’t stop at knowledge. In ethics, he offered something even more profound. Most moral systems before him were about consequences (do what brings happiness) or divine commands. Kant insisted morality must be rooted in reason alone—and in respect for persons as ends in themselves, never mere means.

His famous Categorical Imperative is beautifully simple yet endlessly demanding: Act only according to that maxim whereby you can at the same time will that it should become a universal law. In other words, ask yourself: Could I wish everyone acted this way, always? If not, it’s wrong. Another formulation: Treat humanity, whether in yourself or others, always as an end and never merely as a means

There’s no wiggle room for convenient exceptions. Lying, even to save a friend, undermines the very possibility of truth-telling. Duty isn’t about feeling good or getting rewards—it’s about the quiet dignity of doing right because it is right.

Later, in the Critique of Judgment, Kant turned to beauty and purpose. He saw aesthetic judgment as a bridge between the rigid laws of nature and the freedom of morality. When we call something beautiful, we’re not just expressing preference; we’re sensing a kind of harmony that feels universal, yet disinterested—pure delight without possession.

Kant’s influence is impossible to overstate. He didn’t just answer old questions; he changed the questions we ask. Science gained firmer ground. Ethics gained a secular yet absolute foundation. And we all gained a deeper respect for the quiet power of human reason—and its limits.

Reading Kant can feel daunting—his prose is dense, his arguments intricate. But beneath it all is a gentle optimism: we may not grasp the infinite, but in our finite way, we can think clearly, act rightly, and find wonder in the world we’ve been given.

If you’ve never dipped into him, start with the Groundwork for the Metaphysics of Morals—short, luminous, life-changing. Or simply sit with the Categorical Imperative for a quiet moment. It has a way of lingering, like a clear bell in the mind.

What draws you to philosophy? Kant, for me, is the reminder that thinking deeply isn’t a luxury—it’s how we honor our brief, astonishing time here. 🌿